The mix of COVID-19, an economic downturn and the roll-out of Universal Credit is likely to drive rent arrears among social tenants to record highs. Our estimates based on YouGov polling for the Resolution Foundation suggest that 590,000 working-age households in social housing are in arrears.

Although the recent rise in rent arrears in social housing is less than in the private rented sector, our estimates put the increase since 2018/19 at 180 per cent (circa 260,000 households). Worryingly, arrears among social tenants may carry on increasing, leading to higher levels of homelessness and extra costs to social landlords.

We are, however, still in very uncertain times. Until the emergency measures – and the Job Retention Scheme in particular – are phased out completely, it will be difficult to know how many social tenants might face unemployment or loss of income, and therefore possible rent payment problems. But even a short-lived recession will have a disproportionate impact on social tenants, many of whom are in precarious employment or work in sectors affected by social distancing and are unable to work from home.

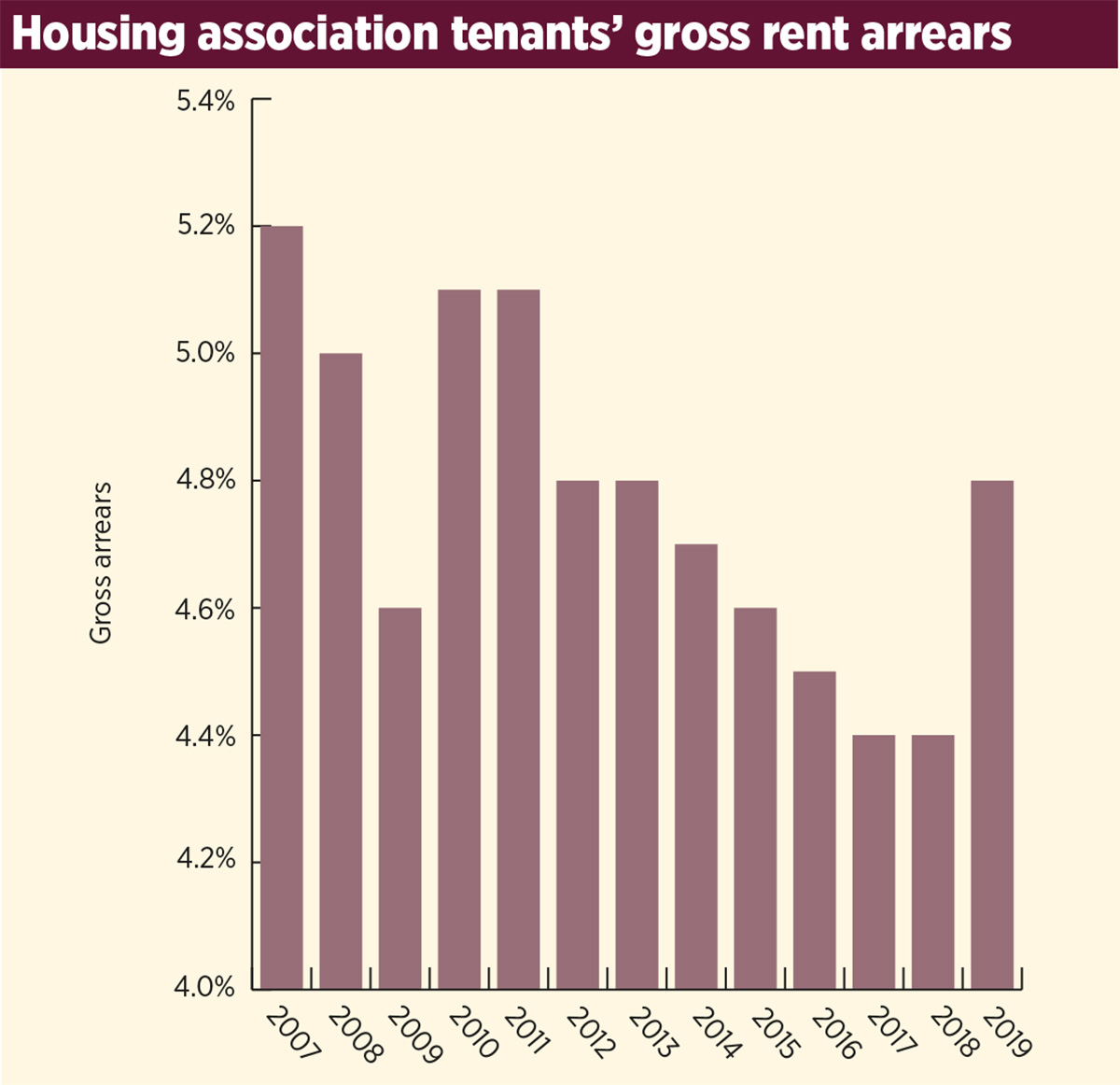

The rise in rent arrears for working-age households has clearly been exacerbated by COVID-19. However, the problem did not start with the lockdown. Latest official data showed rent arrears for all social renters increasing over time – from 14 per cent in 1996/97 to 25 per cent in 2016/17. Gross rent arrears of housing associations have been more cyclical, although they rose sharply in 2019 (up from four per cent in 2018 to 4.8 per cent) after a steady decline since 2013. This seems like a small increase, but on the global accounts it equates to around £50m of rent owed.

If rent arrears rise again to the levels seen in 2007 (5.2 per cent) that would be an additional £50m of arrears for housing associations and their tenants alone.

One difference from the global financial recession will be Universal Credit. Administratively, the system coped under the weight of new claims. However, it is less clear how effective it has been at supporting people as they face a sudden drop in their income and make a claim.

Both quantitative and qualitative research that the Smith Institute has undertaken over the past five years has shown how tenants struggle to pay their rent as they move on to Universal Credit and wait for their first payment.

In the first week, three in four tenants underpay their rent and during the initial weeks large rent arrears build up – which tenants struggle to pay back.

Our rent account analysis in London has shown that average rent arrears for social tenants totalled six per cent of rent owed over the 12 months after they claim Universal Credit, with arrears plateauing over time but not falling. This compares with three per cent of rent owed under the legacy housing benefit system – where payments were made directly to landlords.

The prospect of a large increase in arrears therefore appears very real when looking at the official data.

Department for Work and Pensions evaluation of the new Universal Credit housing element claims are still emerging, but based on the data available it seems there could have been around 700,000 net additional claims between March and May. Evidence from our rent account analysis suggests this could equate to an extra £100m in rent arrears this year.

The need for a responsive and effective safety net to combat this increase is evident in the data on social tenants’ lack of resilience to financial shocks.

According to the English Housing Survey, 83 per cent of social renters do not have any savings or investments. Many tenants already have multiple debts. Research for the Affordable Housing Commission (AHC) showed that large numbers of tenants could not pay their rent if they lost their job – as we are witnessing now – suggesting that Universal Credit needs to help people immediately.

Rising levels of arrears associated with Universal Credit will hopefully engender further scrutiny of the system. In particular, there may be renewed calls to reduce the five-week wait for the first payment.

This would take time to deliver as it is built into the system (Universal Credit currently relies on payroll information) and will come too late for the hundreds of thousands of new claimants. However, if fast-tracked, it might just be able to support those affected by any second wave of job losses.

The immediate challenge will be how to address the repayment of arrears. Our rent account research suggests tenants find it hard to pay down arrears, even with supportive payment plans and debt recovery practices. To avoid evictions – often costing much more than the rent from a tenancy for a year – additional resources will need to be deployed to prevent arrears arising and increasing.

Social landlords will be faced with tough choices regarding rent levels. After years of freezes and cuts, most social landlords were planning to increase rent levels under the new rent standard. Many will now be under pressure to review their business plans about rent levels and projected rental income. The focus, though, for the short term will surely be on supporting the newly unemployed and helping working tenants to repay arrears accumulated during the lockdown.

The situation would be helped if the recession is brief and the recovery is ‘V-shaped’. Conversely, a deep and prolonged recession with higher unemployment levels than 2008 – alongside the long wait for Universal Credit – could see arrears escalate significantly. This scenario, given the already high rate of arrears, would create major problems for some social landlords and misery for tens of thousands of social tenants.

Paul Hackett, director, Smith Institute, secretary, AHC

This article first appeared in Social Housing magazine